Guiding Principles of Emergent Early Childhood Education

| March 2022When speaking with prospective parents interested in the child development center I manage, I often get asked, “What curriculum do you use?” In fact, when I first joined the staff five years ago, I was asked this question not only by parents, but by our very own teachers. I soon learned that the staff, under the guidance of the former director, were planning to take a deep dive into a purchased curriculum.

Don’t misunderstand me; the adoption of one of several research-based, child-centered published curriculums can add marketability and perhaps even enhanced quality to an early childhood program. Yet, I yearned to develop our own process for learning, worthy of our university setting, which would emerge organically from our staff and the very community we served. I wanted us to write our own story. For all those up for the challenge, we were about to embark on an incredible journey of discovery, reflection, and validation.

The Journey

As we explored our best practices, values, and daily activities, our investigation led us to “rediscover full-hearted teaching and learning that braids theory and practice.” (Pelo and Carter, 2018) Together, we were “reimaging a world of early childhood education characterized by open-hearted, attentive collaborations between children and educators . . . moving beyond the joyless land of prescribed curricula with its corresponding outcomes and assessments, into unpredictable, green-growing terrain of lively curiosity and rigorous critical thought.” (Pelo and Carter, 2018) We had an opportunity to set an example in best practices and further define the shape of our program, and early childhood education overall.

The first step led us to examine our philosophy of education. We gathered information about our methodology and practices. But how could we ensure that our philosophy translated into learning and growing for young children? About this same time, I attended a leadership training hosted by NAEYC. As part of the training we visited the National Building Museum in Washington D.C to experience an installation known as Hive. Entering the museum, I came head on into three, floor-to-ceiling dynamic domed chambers constructed of, I would later learn, 2,700 individual, hand-wound, interconnected paper tubes depicting the complex and miraculous workings of a beehive.

"Hive"

Quite the wonder of nature, bees construct their hive using a specific pattern of cellular honeycomb which is encoded in their DNA. I suddenly realized how we were going to bring our educational philosophy to life. I had a framework for presenting to our teachers our program’s pedagogy in action: OUR PROGRAM WAS THE HIVE, and TEACHERS AND FAMILIES WERE THE BEES.

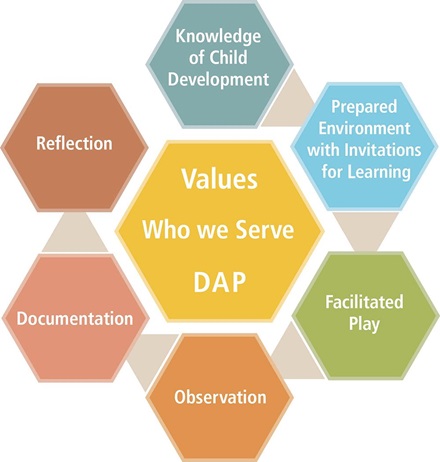

Our Beehive construction plan, encoded in the DNA of our program, consists of our educational values and the diverse family cultures of its community. The Hive exhibit helped me realize that in order to construct the language that explains our methodology, as a team we would need to clearly define two things: the DNA of our program and how we imprint it on day-to-day experiences with children and families. As a team we explored the following questions:

- What values describe our program’s community?

- Who do we serve?

- How will we support brain development and developmentally appropriate practice?

When we considered our community values, we reflected on the original mission of our school, what we each believed valuable to our work, such as respecting all children, and how we strived to interact with others in our community. Who we serve, we agreed, is cyclical as one school year flows into the next, but consistently, each new year brings renewed diversity in cultures, family structures, and languages, all of which, should be represented. Lastly, we acknowledged the environment combined with developmental milestones as the foundation to supporting developmentally appropriate practice (DAP). The way in which we construct our learning environments dictates the emotion and behavior of the children using them. Additionally, “classroom environments are public statements about the educational values of the institution and the teacher.” (Tarr, 2004) Environments reflect the teacher’s values and passions, as well as the children’s interests, curiosities, and family culture. With intentionally prepared environments we provide the base for building rich experiences which support brain development and developmentally appropriate practice.

Once we defined our program’s DNA, we could develop the physical structure of our hive, or in other words, a process of implementation that illustrates the goals and expectations of our philosophy. The “Hive” symbolized the learning environment, or in the broader sense, our program’s culture. We needed to establish how our programs DNA would play out in the actual classroom. What did we need to do to show our values, culture, and philosophy?

The following structure helps to scaffold the experiences and interactions within the learning environment and nurture continued growth of both the student and the educator.

1. Knowledge of Child Development

Although every child develops at a unique pace, as educators we must understand general milestones of child development to ensure our decisions and interactions in the classroom are based on realistic expectations. Additionally, a clear understanding of child development supports a teacher’s process of developing a safe and meaningful learning environment that nurtures each child while also challenging their continued development.

2. Prepared Environment and Invitations for Learning

“Frederick Froebel described his approach to organizing and offering materials as ‘gifts’ for learning. Reggio Emilia [practitioners] talk of ‘provocation’ and have given us innovative ideas for kinds of materials that engage children and careful, aesthetically beautiful ways to display them.” (Curtis, 2004) Young children effectively engage in the learning process when the environment is well organized with purposeful materials chosen intentionally based on our previous reflections of their play and work samples. “The way materials and props are offered is as critical to their use as what is offered.” (Curtis, 2004)

3. Teacher Facilitated Play

Within the prepared learning environment, a teacher’s role as facilitator of play is essential. Although observations of children engaged with learning materials provides critical information about the effectiveness of the room arrangement and materials chosen, our interactions with children during play creates the magic of an early childhood classroom. Without the teacher’s open-ended, thought-provoking questions, offerings of additional materials to enhance play, and a genuine collaboration with children, the play remains flat and absent of the scaffolding of new skills. In the words of John Dewey, “[The] teacher operates . . . as a friendly co-partner and guide in a common enterprise.” (1934)

4. Observation

Throughout the activities and routines of the classroom, teachers record conversations, observations, and questions. Such evidence, when later reflected upon, uncovers ideas and understandings of children, the environment, and themselves all of which should then be used when planning for learning. Emergent curriculum requires our teachers to support and guide learning as it emerges naturally.

5. Documentation

Written observations combined with children’s work samples and photographs create the evidence of learning. Lella Gandini stated, “Documentation is ongoing and part of planning and assessment. It encourages children to revisit an experience and to share a memory together. It can provide opportunities for further explanation or new directions.” (Tarr, 2004) Documentation provides the elements for reflection.

6. Reflection

The end of the emergent process of learning is also the beginning, for it is through reflection that “we shift our focus from instruction to inquiry―from teaching to thinking―we commit ourselves to creating possibilities rather than pursuing predefined outcomes.” (Pelo and Carter, 2018). Reflection offers an opportunity to examine and question. At times we emerge with answers that shape further learning experiences, yet often the questions themselves mold the mutual discoveries that lie ahead of both child and teacher.

This process for implementing an emergent early childhood philosophy remains open to evolution with each new child, family, and teacher. Yet, it also offers structure and essential guidelines for the teacher and program to ensure meaningful, developmentally appropriate play is recognized as a child’s work and utilized as the vehicle of growth and learning. The Emergent approach to learning develops organically from the interests of the children, and our knowledge of each child's development. Utilizing educational philosophy based in decades of research provides the necessary framework to ensure emergent practices develop with meaning and intention. Philosophies such as Reggio Emilia, nature-based play, loose parts, Bank Street's developmental-interaction approach, to name just a few, when considered within the practices of an emergent, play-based, child-centered program, create just the right formula to provide engaging, meaningful, and inclusive early childhood experiences.

The task of education is to inspire learning that shapes both personal development and human connection so to improve the potential of not only the individual but our interactions with one another and our planet. Let us embrace the potential of an emergent teaching philosophy to best honor and nurture the true potential of young children, their teachers, and their communities.

References

Curtis, Deb. (May/June 2004). “Creating invitations for learning.” Child Care Information Exchange.

Dewey, John. (1934). “The need for a philosophy of education.” The New Era.

Felstiner, Sarah. (May/June 2004). “Emergent environments: involving children in classroom design.” Child Care Information Exchange.

Tarr, Patricia. (May 2004). “Consider the walls.” Beyond the Journal: Young Children. NAEYC.

Pelo, A. and Carter, M. (2018). From teaching to thinking: a pedagogy for reimagining our work. Exchange Press.