The Ordinary Magic of Resilience

| May 2023Once upon a time, children laughed gleefully as they chased “dragons” away from their castle on the playground. Princesses tended their babies in the dramatic play area, while Cinderella swept the floor. The slide became the beanstalk as Jack and his courageous friends, Jill and Jamal, climbed to the top to see if they could sneak into the giant’s house. When they didn’t spot him, they zoomed down, cradling imaginary gold in their arms.

The Problem

Sadly, over the past decades, such scenarios have become increasingly rare. The large blocks of playtime that allow for imaginative storytelling have been whittled into tiny splinters in many programs, while concern for academic preparation has become the priority. Families flock to Disney franchise fairy tales, while simultaneously, many are concerned that reading fairy tales to their children will scare or scar them. In the 15 minutes of time they are allowed to play freely with their friends, young children are left to regurgitate fairy tale plot fragments they’ve watched on screens.

What’s the big deal, you might ask? Aren’t fairy tales outmoded and filled with all the “isms” we want young children to avoid: sexism, ageism, Eurocentrism? Do they teach effective problem-solving? For example, what if instead of shoving the wicked witch in the oven, Gretel had appealed to her higher nature and convinced the old witch to release her and her brother because it was the right thing to do? Aren't children better off without stories of violent heroism?

In fact: no.

It is no surprise to anyone working with children that many are experiencing significant difficulties. Even before the pandemic, teachers (and parents) were concerned about the increase in challenging behaviors. Children seem unable to sit still. There is more pushing and shoving, more angry outbursts, more tears, and more distractibility, even during “fun” activities. Both anecdotal evidence and research indicate these problems are increasing as children come back into early care and education settings as the pandemic has waned.

Why?

Many experts point to toxic stress as one major source. Toxic stress is the response of the brain to chronic or traumatic stress. We have heard a lot about trauma, and ACE (Adverse Childhood Experiences), which include things like child abuse, domestic violence, and family substance use disorders. These traumatic events throw the brain into “fight, flight, freeze, or fawn” mode, our bodies’ natural response to danger. Research on toxic stress indicates that the brain can respond in the same way when the stressors are not as dramatic, but are constant, thus depriving the child of the opportunity to bring their stress responses back down to normal.

As we search for ways to support children and regain the joyful classroom communities that nurture learning and development, the “ordinary magic” of resilience bubbles up as a possible solution. Resilience is the ability to bounce back from adversity, in whatever form that may take.

The Magical Elixir of Resilience

What are the secret ingredients in this magical elixir of resilience? Researchers have scrutinized why some children who experience trauma have far better outcomes than others. These studies focus on relationships and resilience as primary protective factors against toxic stress. After analyzing many research studies, including the work of resilience scholar Dr. Ann Masten, Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child (2015) compiled a set of key factors that build resilience (Masten, 2014).

Resilience Factors:

- Relationships: A relationship with at least one stable, caring, and supportive adult (either a primary caregiver or another adult), as well as peer relationships

- Initiative: a sense of control over circumstances (includes self-efficacy, problem-solving and motivation to succeed)

- Strong executive function and self-regulation skills

- A supportive cultural/faith context (includes the music, food, stories, traditions and customs from the child’s home culture, or the culture of the community)

This is wonderful news for those of us in early childhood! To nurture resilience in children, we can follow the principles of developmentally appropriate practice:

Focus on relationships.

Give children lots of opportunities to have their wonderful ideas and act on them (let’s hear it for play!) Support the growth of their self-regulation and executive functions by offering engaging environments and scaffolding as they learn to focus, problem-solve, and become part of a group.

Do all this in a context that honors the diverse backgrounds of their home cultures.

Reach for your Magic Wand

What does this have to do with fairy tales? Fairy tales are stories of overcoming seemingly insurmountable odds to reach the happily-ever-after resilience brings. Fairy tales feature magic that fuels young children’s growing understanding of the world. One of the “fairy godfathers” of our field, Jean Piaget explained that children engage in “magical thinking” until they reach the elementary years.

Quite simply, they believe in magic and animism because they have not yet constructed the mental schemes to understand causality in the physical and social worlds. A ball bounces because it likes to jump around; a beautiful rock appears in their path because a fairy put it there. The young and disadvantaged fairy tale characters are the ones who outwit the bad guys and go on to save the day. The ability to rise above challenges is core to both fairy tales and resilience. The very ways that young heroes and heroines overcome overwhelming odds are beautiful examples of the protective factors of resilience.

Think about Hansel and Gretel. Two siblings are left in the woods, captured by a witch, and they return home triumphantly, in part, because they are steadfast in their commitment to helping each other (resilience factor: relationships-peer). Hansel uses his wits and leaves a trail of white rocks so they can find their way home. Gretel sees that the witch is trying to fatten up Hansel and tells him to hold out a chicken bone when the blind witch tests his finger for plumpness each day (resilience factor: initiative). Although there’s lapse in the protective factor of self-regulation when they succumb to temptation and nibble on the witch’s house, the children demonstrate their ability to control their actions and emotions throughout the rest of the story. They stay focused on getting home safely even when they are frightened and confused. Gretel ends the witch’s evil plans when she courageously tells the witch that she can’t reach the bread in the oven, asking the witch to check it herself. Thus, it’s no surprise children want to incorporate these strong and resilient characters into their play.

The shared story language and imagery of fairy tales invite children to take the stories and integrate what they know about relationships and the way the world works. A child who wants a pet will make sure that there’s a puppy in Cinderella; a child who has just moved may build the rooms in the Three Little Pigs’ houses in the block area.

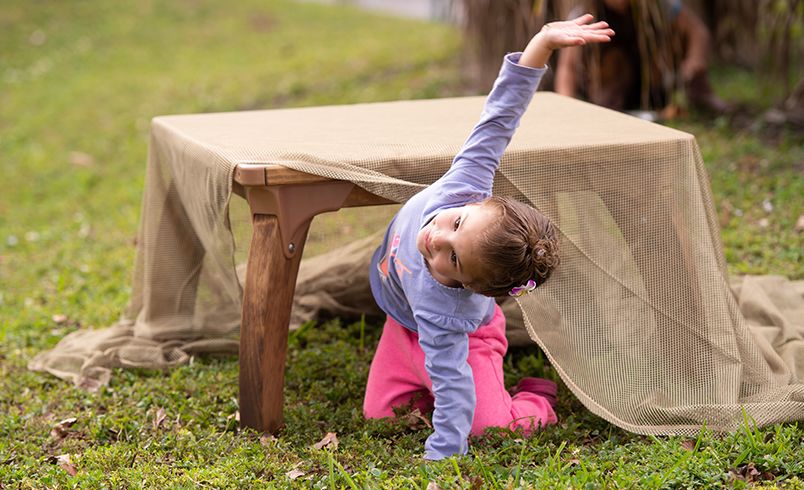

“Quick, let’s hide! It’s the giant!” often becomes story code for children to coalesce into a group with a common goal and support each other’s ability to successfully keep quiet and still (a kind of co-regulation) until someone takes the play in a new and exciting direction. Children immerse themselves in these fairy tale worlds, though, not because they want to develop their own resilience but because fairy tales are, quite simply, good stories. Most have been told in one form or another for hundreds of years, and the themes and plots are similar throughout diverse cultures on every continent. They also have clear-cut plot structures that offer young children a model for play, as well as emergent reading and writing skills.

Wave your Wand

How can you maximize the extraordinary magic of fairy tales and channel it into the ordinary magic of resilience in your early childhood setting? While there as many ways to do this as there are snowflakes in the land of the Snow Queen, here are some strategies to get you started:

- Go to the public library and talk to the children’s librarian. They can help you find stories that best match your children’s ages and interests, as well as multicultural variations.

- Sidestep the “Fairy Tale Week” trap. Research tells us that for in-depth connections, children do best with repeated readings of the same story. Reading five versions of Cinderella over the course of a week is a better option for promoting resilience and literacy than reading five completely different fairy tales during the same week.

- Plan your classroom environment with materials that scaffold children’s curiosity about the fairy tale they are exploring.

Materials to consider for each learning center:

Classroom library

- Display many versions of the same fairy tale

- Puppets

- Felt board characters that support retellings.

Dramatic Play

- Open-ended dress-ups such as scarves, belts, and boots to inspire a wide variety of fairy tale characters.

- Add art materials. For example, cookie cutters and construction paper scraps for snipping may encourage children to exhibit the bravery of Hansel and Gretel as they create a candy house.

Blocks

- Add spools, paper tubes, aluminum foil scraps, loose parts, and farm animals to inspire castles, farmhouses, and other structures.

- Display fairy tale books with different architecture: children may use unit block shapes that they haven’t considered before.

Discovery Area

- Add nature items related to stories: e.g., droopy roses (Beauty and Beast); pumpkin (Cinderella); beans (Jack) etc.

- Include magnifying glasses, eye droppers, tweezers, scales, and other tools to examine the objects.

Story/Writing Center

- Small, medium, and large sized paper, along with small, medium, and large markers, pencils or crayons (e.g., Three Billy Goats Gruff).

- Envelopes and sticker stamps (Notes from Rapunzel; invitations to the ball etc.)

Playground

- Bring out your boat/bridge wooden structure so children can create their own take on Thumbelina or Tom Thumb, Three Billy Goats, etc.

- Pebbles and baskets and sticks in the sensory area for small world creation

The possibilities are endless, and as children’s playful connections to each fairy tale grow, they will inevitably take over the generation of great ideas (resilience factor: initiative) while engaging in rich social play (resilience factor: relationships and self-regulation). And you will be helping children tame any trauma dragons they may be dealing with, ensuring that each child can be “happily ever resilient” as they skip through whatever dark forests they encounter.

References:

Center on the Developing Child (2015). The Science of Resilience (in Brief). Retrieved from www.developingchild.harvard.edu.

Masten, A. S. (2015). Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Resources:

For a full collection of resources on resilience from Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child, click here.

For a Ted Talk-type presentation on the ordinary magic of resilience by Dr. Masten: Watch here.

Stephanie Goloway’s book: Happily Ever Resilient: Using Fairytales to Nurture Children Through Adversity. Red Leaf Press. 2022.

Read the Book!