Walking the Talk of Collaboration

| December 2010Collaboration is not a passive phenomenon; it requires risk taking with some passion about it. Collaboration that leads to meaningful learning often begins with someone's (or something's) act of provocation and the willingness of another to become engaged. (Elizabeth Jones and John Nimmo)

Collaboration has now become one of those buzz words in our field, referring to a variety of efforts to bring people together for shared goals, projects, or tasks. Funders and policy makers favor collaborative efforts among organizations with proposals to improve quality and academic outcomes. The growing voices of those influenced by the Reggio approach emphasize the importance of collaboration among parents and teachers, teachers and teachers, teachers and children. But in a country like the United States, founded with a mandate to preserve the rights of individuals, how does collaboration take hold and what does it look like, especially in the everyday life of an early childhood program?

True collaboration requires a set of dispositions, beliefs, commitments, and skills. Even then, it isn’t easy to collaborate, especially across significant differences in cultural perspectives, experiences, personal, or organizational histories. Above all, collaboration takes time, something rather scarce in most of our child care programs. Are there models we can look to? What strategies nurture the dispositions and skills to collaborate and build an organizational culture of collaboration?

Right from the Start

To acquire a desire for and the ability to collaborate, most of us need some serious retraining of our minds and mouths. There isn't much in our overall culture that develops us into collaborators. To the contrary, so many things conspire to pull us in the opposite direction toward competition, complacency, defensiveness, or disregard for the collective body. It takes a concerted effort to discover the deeper benefits of collaboration and unlearn the attitudes and behaviors that undermine it.

Consider the organizational culture of your program. Do your policies and standard practices reflect and reinforce the value of collaboration? What things need revamping to be consistent with notions of collaboration? When families first visit your program or potential staff members arrive for an interview, how will they get a sense of the value you place on collaboration?

Strategy: Hold group visitations and interviews

Traditional approaches to touring families through a program or conducting staff interviews involve an individual meeting with the director where she or he poses questions and tries to market the program as the best place in town. What if, instead, these were group experiences where, for instance, prospective families considering your program were offered a day of the month where they could visit and not only hear from the director, but a current parent in the program and the others who came for a tour? In this arrangement different perspectives, priorities, and concerns could be considered and dialogue among all encouraged. The process could be one of exploration, getting questions and ideas from others and discovering the value of the opportunities your program offers families to come together to learn from each other's perspectives.

Likewise, if a small group of potential staff members are asked to come together to learn about a job opening and there is an open discussion of values, how we see children and families, team work, and the teaching and learning process, candidates get a direct experience of the collaborative discussions that are essential to your program. And you get to watch them in action as they share their ideas with others. A few activities and scenarios typical to your program could be presented as a mock team or staff meeting. You could discover how people approach these collaborative discussions and demonstrate how you support and encourage them. You could ask more unconventional questions such as, “What new idea did you get from someone here?” or “How do the approaches discussed here compare with your own upbringing?”, along with more typical ones such as, “What experiences have you had that influence how you might solve this problem?” or, “Are there questions or concerns you would like addressed?”

Offering group experiences right from the start to prospective families and staff holds the promise of uncovering whether your program is a good match for them. Are they put off, intrigued, or pleased by this experience? These discoveries can be both a marketing tool for your program and a time and heartache saver for the director. You can offer to schedule additional individual meetings to explore specific concerns or more personal questions.

Collaborative Relationships With Families

To invite the families in your program into a collaborative relationship with each other and the staff, they need to be initially greeted with something other than a stack of paperwork to fill out. Genuine relationships grow out of mutual interests and respect, not a one-way stream of information, questions, or requests. Home visits are a wonderful way for teachers and families to begin to get to know each other; but when these are done, they typically reflect little indication of a desire for collaboration. What if the families were given the opportunity to meet either at their home or that of the teacher? What if the family was invited to ask questions about the teacher, in addition to the teacher’s questions of the family? How can the nature of the questions reflect the goal of collaboration rather than a focus on policies, needs, or program details?

Strategy: Begin new traditions

I’ve been seeing some wonderful traditions emerging in programs which translate into an invitation to collaborate in making this program comfortable for them and reflective of their family:

- Asking families to each bring a plant to line the playground fence or windowsills to form friendship gardens and surround children with the gifts of mother nature.

- Providing paint your own materials for families to make teacups, lunch plates, or placemats for their children in the program.

- Exchanging photo stories (perhaps with the loan of a camera) about weekend or holiday experiences away from the program.

- Sharing favorite childhood memories at meetings and exploring how to bring these into the program.

- Holding staple-gun and Velcro(r) upholstery parties where second-hand overstuffed chairs, love seats, couches, pillows, and lamps get quick, collective face-lifts to improve the softness, aesthetics, and comfort for adults as well as children in programs.

- Creating collaborative recipe, song, or story books where we get a glimpse into favorite traditions and stories that each person has to share.

Strategy: Find meaning together

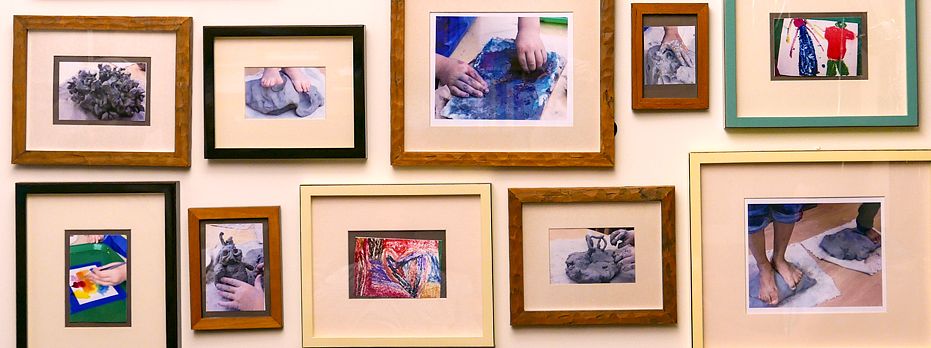

Programs which gather documentation for portfolios or displays often use these observation stories, work samples, and photographs to communicate to families the activities and developmental progress of their children. But, rather than serving as evidence for a conference report or assessment, what if documentation, instead, became a tool for collaborative discussion among staff and staff and the children’s families?

In their inspiring chapter, “Developing a Sense of ‘We’ in Parent/Teacher Relationships” Carol Bersani and Debra Jarjoura (2002) describe the attitudinal and organizational changes they began to make at their school with the goal of making it more collaborative with parents. They asked themselves, “Did we confuse collaboration with cooperation or congeniality?” A significant change they made was to invite the parents to join them in looking more closely at the documentation of project work, to construct its meaning together. This eventually led to parents volunteering to document experiences in the classroom, and later to the formation of group parent/teacher conferences. By the end of the year they began to notice a shift in the parents’ focus from “How is my child doing in school?” to “What are the children thinking and doing in school?”

Ongoing Opportunities to Learn About Collaboration

As Elizabeth Jones and John Nimmo so clearly remind us, “Collaboration is not a passive phenomenon.” Nor is it something you can check off on your strategic plan or assessment tool. Rather, it is an ongoing work in process, with all the highs and lows of the collective human experience. Supporting teachers to collaborate requires the steady building of an organizational climate and the skills to listen and question, negotiate conflicts, and live with disagreements. It requires that hard to come by resource of time to regularly be together and a commitment to dismantle the barriers that get in the way. Give teachers ongoing opportunities to practice collaboration and to deepen their understandings of how this differs from our notions of involvement, cooperation, or congeniality. Rob Lehman sums it up this way:

“Collaboration, on the surface, is about bringing together resources, both financial and intellectual, to work toward a common purpose. But true collaboration has an ‘inside,’ a deeper, more radical meaning. The inner life of collaboration is about states of mind and spirit that are open . . . . And human collaboration that draws upon the resources of mind and money, but not on the resources of grace, will only rearrange the furniture.”

References

Bersani, C., & Jarjoura, D. (2002). "Developing a Sense of 'We' in Parent/Teacher Relationships" in Victoria Fu, Andrew Stremmel, Lynn Hill, Teaching and Learning. Columbus: Merrill Prentice-Hall.

Jones, E., & Nimmo, J. (January 1999). "Collaboration, Conflict, and Change: Thoughts on Education as Provocation." Washington DC: Young Children, NAEYC.

Rob Lehman quote found in the brochure for Interaction Institute for Social Change. Boston: IISC.

Article used with permission from Exchange Magazine, http://www.childcareexchange.com/